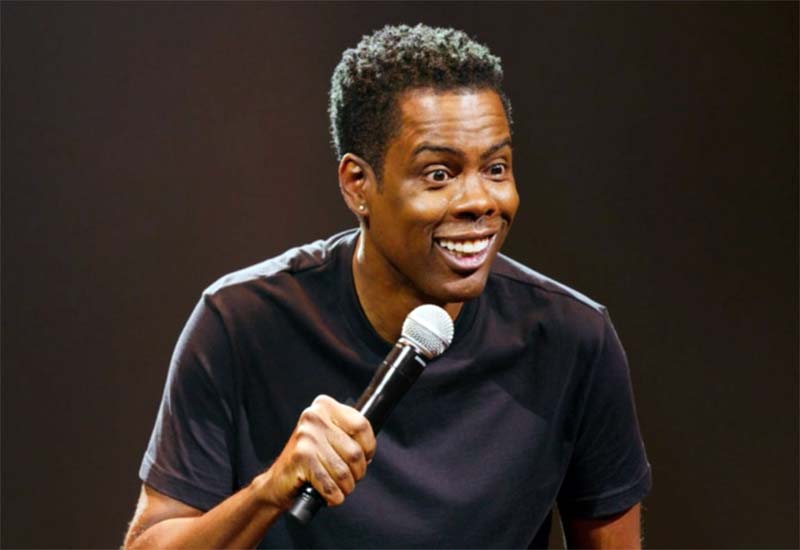

Chris Rock remains the king of metaphor. In his latest special, Tamborine, Rock immediately launches into masterfully dark, twisted, and absurd solutions to American injustices. In one of his most notable bits, Rock tasks the alleged democracy of the United States to enact equality in all aspects of American life and extend state sanctioned murders of the nation’s youth to white kids. His description of white mothers on television crying over their children, is so hilariously ironic, I am seriously considering rocking a “Justice for Chad” t-shirt. I imagine that many may find this particular joke about police murdering kids disturbing and the joker, disturbed. It is, and he is. But this trickster we see onstage is merely a reflection of the current state of our society and the ridiculous political ideology that supports the annihilation of people of color.

In addition to offering reform solutions for police enforcement, Rock offers his parenting strategies as a model for how to prepare black youth for the racist world that awaits them outside the walls of their home. He explains, “I’ve been getting my kids ready for the white man since they was born.” Rock then describes the ways in which he psychologically primed his daughters on the dangers of literal whiteness, by making everything white in his house, “hot, heavy, or sharp.” Painting vivid scenes of the pain that his toddlers suffered as a part of this “white-a-drill” training, Rock conjures another moment of laughter that communicates a multiplicity of emotions and truths that go beyond laughing at my pain. It asks us to consider the physical harm and psychological trauma that black children must endure in order to survive.

On one hand it is terribly cruel, but on the other knowing how to deal with racism is a skill that we must try to equip our children with, no matter how fraught the endeavor. So while we wince and grimace at the description of toddlers and children experiencing intense physical harm at the hands of their father, we laugh at the symbolism. White supremacy is a hot toilet seat that burns your ass. It’s a 150 pound onesie that breaks your back. And it is glass filled dessert that cuts up your tongue and throat. “That’s what whitey do.”

In true Rock fashion, his performance is marked by high energy punctuated with continuous movement; if you remember his Bring The Pain stand-up, you will notice he hardly stood still. Of course, age has probably slowed him down a bit, but his trademark intense energy and back-and-forth pacing across the stage enhances/infuses/impregnates his brilliant, comedic material.

It is the intentional absence of this energy that makes the second half of his new act feel like an entirely different performance. In this half, he hones in on the personal, giving advice about relationships and deconstructing the deterioration of his own marriage. Laughs become secondary as they function mainly to break the serious tone of his performed vulnerability. His shift from national critique to confessional is also marked by his lack of movement. Compared to earlier, Rock is practical still.

There is a scripted slow down indicated by an extreme close-up. Because Rock is so embodied, so physically animated, audience members understand this as a scripted, preconceived moment of stillness communicated between the performer and the production crew in need of capturing the moment. This is atypical to the genre of stand-up. Yes, close-ups are common as it is often important to capture the details in the comedian’s face. This one is different; it lasts for much longer, his entire face fills the frame, and he is not serving the punchline of a joke, but rather the setup, which in this case is his declaration that he cheated.

With this tight framing of his face, a Rock we have never before seen on stage is being birthed. He admits his transgressions, takes ownership over the fact that he was not a good husband, and publicly mourns the death of his marriage, predominantly in a non-comedic tone. This is not only significant as a new style for him, but also represents a shift, a deviation from the aggressively sexist moments peppered throughout his previous stand-ups.

While I have my own gripes with Rock because of the aggressively sexist jokes he made in his earlier performances, this vulnerability, these admissions of shortcomings (combined with the choice to have up-and-coming black women comedians like Yvonne Oriji open for him) shows promise. It is likely that we are looking at a transforming Rock who no longer feels a need to go so hard on black women. For me, all is not forgotten, but I do acknowledge and appreciate his comedic genius and I am interested in experiencing his continued evolution as both a man and a comic.