In the beginning of the summer’s heat, I headed down to New York for the first time. It would be a 10 day trip, with little on the itinerary–I planned on finding my way around the grand state with the help of a good friend, who graciously allowed me to become her temporary roommate. With both of us being visual artists, it went without saying that viewing art would be of tremendous importance during my stay.

After being picked up at the airport in Queens, we went to a museum close by, located in an unassuming area. With great anticipation, I entered my very first exhibit in New York at MoMa PS1, called rootkits rootwork. Created by interdisciplinary artist Devin Kenny, I found myself in his first solo museum exhibition: an interactive, visual, and sound-based show on racial politics, gentrification, Houston’s hip-hop scene, and more.

The meaning behind rootkits rootwork is interpreted, courtesy of moma.org:

“Rootkits” are a form of computer virus that undetectably alter the underlying operating system; “rootwork” alludes to practices of Black-American folk magic, and both reference the DNA kits that allow people to explore their heritage.”

Titles such as Do you even talk to your neighbors? (2018) and Juneteenth rap explosion (2018) captured my eye, and I promptly became engrossed in Kenny’s work–even though my non-black friend had long left the exhibit. As you walk in, you’re greeted with a wall dedicated to those We Buy Houses signs that we’re all too familiar with. And yet, as I walked through the show, I came to the realization that I’ve never linked these copious advertisements to gentrification, although this is surely the case at times.

I suppose the concept of gentrification didn’t affect my own life much, as I’ve never been a part of the “before” stages of such a displacing process. I’ve only ever seen such spaces post-gentrified, although I was certainly aware of the elaborate history and culture of cities such as Brooklyn, Harlem, and D.C. With these images of an era before my time in mind, the difference makes such places almost unrecognizable. Yet, the personal and emotional connection just wasn’t there for me, simply because I didn’t watch my own neighbors, or those I grew up with, become forced to move away due to increased rent and taxes.

My mother, who grew up in D.C., often speaks about the gentrification occurring in her childhood neighborhood, but she finds beauty in these newly renovated homes–and I must admit that I do, too. My grandmother, who still lives in this cherished D.C. house after 50 years, also appears to be unaffected by the rapid changes occurring around her. However, this exhibit created an unexpected reaction, as it allowed me to put myself into the shoes of someone who experienced the unfortunately common trauma of being involuntarily uprooted from a home that is all one has ever known.

Devin Kenny: rootkits rootwork runs through September 2.

After my first day in New York, I didn’t go to any other museums for quite a while. This wasn’t by choice, of course, but because of the fact that my friend resided about an hour away from the heart of New York City’s art world. She lives in a rather white area, close to Greenwich, Connecticut. Nonetheless, I made it home, and never once felt like an outsider. Yet, I had a strong desire to be in the midst of culture, to experience more works by artists of color in the city.

One early Wednesday morning, I decided to tag along to work with my friend, who has a studio job at SUNY Purchase. To my surprise, there was a museum located directly on campus by the name of Neuberger Museum of Art. While a majority of the museum was closed for renovation, there were three exhibitions still open, with two centering around black art. Instantly, I recognized that this was a manifestation of my intense desire to find more black art. After all, what are the odds that I stumble upon artworks by people of color in a small town where an insufficient amount reside?

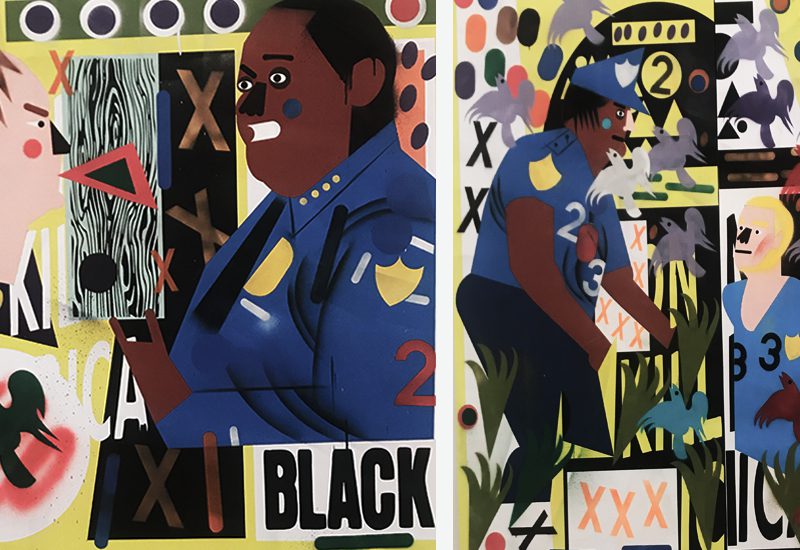

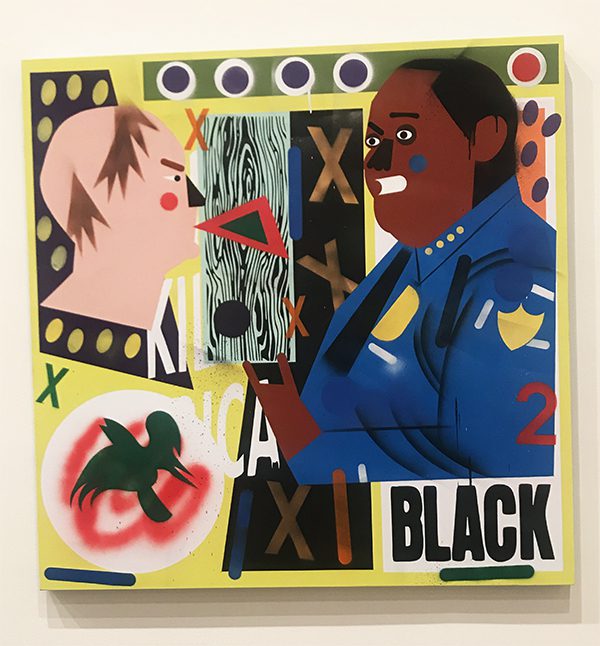

Here, I discovered a gem of an artist: Nina Chanel Abney. The exhibition, titled Royal Flush, is a decade-long survey of the artist’s large and small-scale paintings, watercolors, and collages that articulates racial relations, social dynamics, celebrity culture, and urban life.

In Untitled (XXXXXX), two black officers appear to be calmly arresting a white man. She uses her signature jumbles of shapes and letters to create a sense of confusion, but the word “kill” is there, slightly hidden between the black and white man. This conveys the message that while the interaction is seemingly peaceful, there are aggressive undertones still present.

In 2015, she completed a series of these #BlackLivesMatter related paintings, many of which appeared in Royal Flush. While the works are surely obscure, explicit, and downright bewildering at times, these are the qualities that makes the paintings of Nina Chanel Abney impossible to overlook. With each view, one discovers a new detail that was previously undetected. As a painter myself, Abney encourages me to take unapologetic risks in art, and disturb the comfortable by speaking my truth, however bold this may be.

Lastly, I entered the museum’s permanent African art collection from four major regions: Western Sudan, Guinea Coast, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. African art is so colossal that I’m often overwhelmed by the works, and become unsure of where to even begin. Here, it was divided in such a way that made navigation simple, and the locations that the artworks originated from were always named in great detail, which I appreciated. Instantly, I was drawn to a colorful costume located in the middle of the exhibition. Titled Masquerade Costume (Egungun), it was created in the 20th century by the Yoruba people in Nigeria with fabric, plastic, aluminum, beads, and coins. The stand which holds this intricate piece reads: “You see the costume not the spirit,” a statement that speaks volumes about what I interpreted as the superficiality of humanity, and those who may be fooled by an extravagant, masked appearance, which is only the vehicle for the soul.

A face mask by the Kuba people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was striking. Made around the 19th-20th century, the delicate craftsmanship left me in awe. The precise placement of the colored beads, cowrie shells, and wood carvings makes the mask quite engrossing.

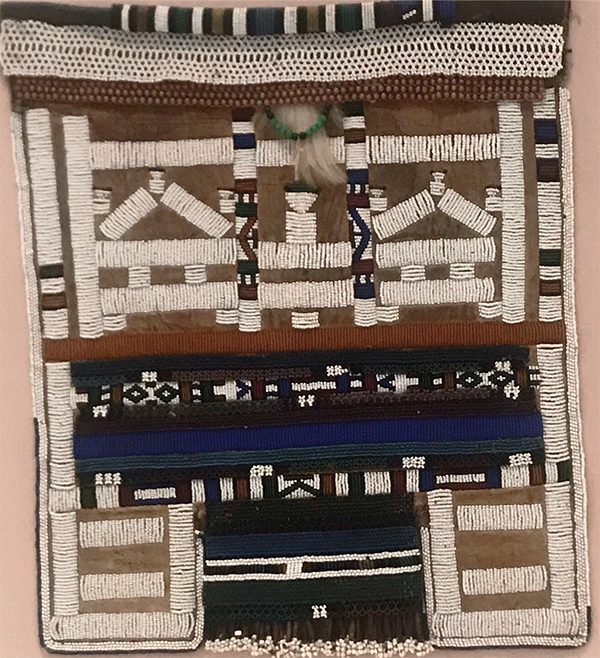

I was drawn to another piece from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, crafted by the Luba people in the early 20th century. This untitled work, created with beads and fabric, is a highly intricate yet quiet piece due to its primarily muted colors. And yet, I couldn’t look away because of how aesthetically pleasing it was. In the details, there are similarities here to South American culture, particularly within rug, jewelry, and tapestry patterns. I personally love when cultures overlap even in the smallest of ways, because it serves as a reminder that we are all connected at the core.

As I reflect upon my journey in New York, I was pleasantly surprised by the areas in which I discovered black art – or perhaps how the art found me. Of course, I’ve barely even scraped the surface of the art that lies within the depths of the city, and yet I can still say with confidence that what I did find was far more unique than any other museum that I have been to thus far. In a future trip, however, I am eager to explore artistic spaces with more intent, and on my own terms.

To learn more about the exhibitions mentioned above, please visit moma.org and purchase.edu.