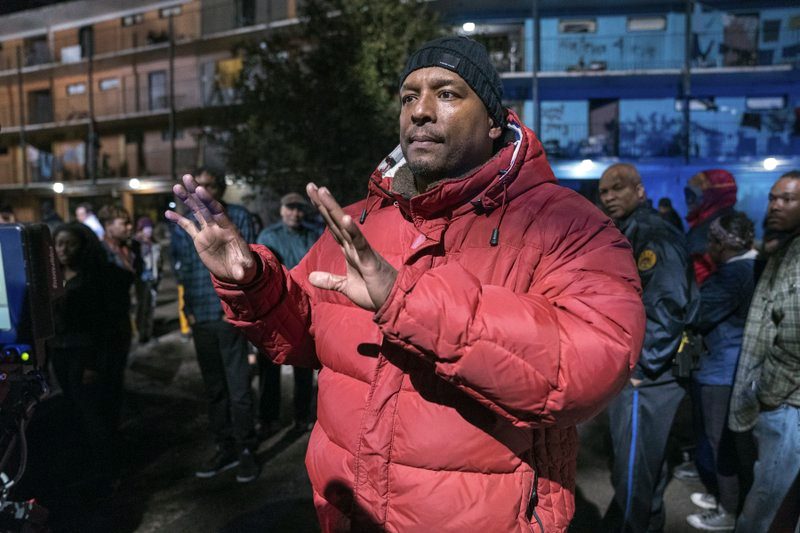

LOS ANGELES — Deon Taylor doesn’t take no for an answer when it comes to filmmaking. And it’s a word he hears all the time.

When no one wanted to make his first film, he made it himself and even persuaded Rutger Hauer to be in it. When the studio said they couldn’t afford Oscar-nominated cinematographer Dante Spinotti for his latest, “Black and Blue ,” Taylor opened up his wallet and paid Spinotti himself. And when he realized the press schedule for his racially themed action film didn’t include places like Dallas, Cleveland, Detroit and his hometown of Gary, Indiana, he made his own plans to reach those markets.

Taylor knows that some people think he’s crazy for all the extra things he does. But that refusal to be dissuaded was the only way this kid from Gary, who never had any formal filmmaking training, was going to become a director. And after 15 years of doing it his way — independently— Hollywood is finally taking notice.

This year Taylor has two films being distributed by a major studio, Sony Pictures’ Screen Gems: “The Intruder,” a thriller with Michael Ealy and Meagan Good that became a solid hit in May, and “Black and Blue,” a fast-paced police corruption tale starring Naomie Harris and Tyrese Gibson, that opens nationwide Thursday night. It’s something he’s just starting to process himself.

The 43-year-old is a bundle of enthusiasm on a recent afternoon in Los Angeles in his Hidden Empire Film Group offices where he’s on speaker phone fielding interview questions with Gibson and Harris from smaller websites (another of his initiatives). His office is covered in posters of his movies, storyboards for his next project, “Fatale,” which is due out next year from Lionsgate, and even a basketball hoop.

The last item is a nod to Taylor’s professional basketball career, where his filmmaking ambition really started to develop. In 1998 he found himself playing under contract in East Germany. It was freezing there and he didn’t speak the language so he spent most of his free time watching the boxes of DVDs that his girlfriend would send him, learning about the craft from the commentary tracks. It was there he came up with an idea for a horror movie, wrote what he thought was a script (“It was a novel”) and when he got back to California decided to fully commit to becoming a filmmaker.

“I completely went like an Aquarius after this dream and forgot everything I was doing in my former life,” he said. “I became consumed by film.”

For six years, he knocked on doors first trying to get someone to make his film and then trying to get money to make it himself. On the journey, he discovered that there were some “lines” in Hollywood that people weren’t prepared to cross just yet.

“I had a horror movie, and I’m a black director,” Taylor said. “I would walk into rooms and they’d be like, ‘What do you got? ‘Boyz n the Hood?’ And I’m like, ‘No I’ve got this great horror movie’ and they’re like, ‘No no, slow down.'”

Along the way he met Robert F. Smith, the billionaire philanthropist, and they started Hidden Empire Film Group, which they run with Taylor’s wife Roxanne Avent. He learned on the fly what he liked and what he didn’t in low-budget filmmaking and that’s when he developed a love for cinematographers and all the craftspeople that make a film look and sound good.

“I’m looking at it like basketball now. You go like, ‘Who’s my shooter? Who plays defense? Who rebounds?'” he explained. “I started looking at film like a sport like, ‘Oh, you got to go get a team.’ And I start searching for stars in that world.”

Movies changed Taylor’s life. As a kid whose family didn’t have enough money to travel, he learned about places and people through films. “Boyz n the Hood” showed him Los Angeles. “Do the Right Thing” did that for New York. And he started thinking about his own projects as a way to educate his 14-year-old self.

“As I grew as a filmmaker I started to think: What are you saying? There are so many filmmakers out here, black and white, who aren’t saying (expletive),” Taylor said. “Adversity became the center of my films.”

With “Supremacy,” he tackled a real life case of a white supremacist who takes a black family hostage; In “Traffik,” it was sex trafficking in the United States. And, for Taylor, it’s all been building up to this moment with “Black and Blue,” which he helped infuse with themes about police distrust and justice.

Harris, who was taking a year-long hiatus after the grueling promotional tour for “Moonlight,” said she came back early to work with this “maverick” director.

“Everybody got really emotionally invested in the movie in a way that I haven’t seen on any other movie set,” Harris said. “And that’s all Deon because he sets that tone.”

Taylor’s films also routinely make their money back and then some, but they have another common thread too: Bad reviews often follow. Besides, “Black and Blue” — currently his highest-rated — they’re all under 35% on Rotten Tomatoes.

“They’re independent, risky films and everyone doesn’t get it. I remember making ‘Traffik’ and thinking, ‘They’re going to hate this,'” he said. “Not the people, but the people that write are not going to understand what’s going on in this movie… It’s very often that a certain group of critics get it and a certain other group does not.”

He likens it to how Tyler Perry’s films are received by critics versus the people who go out to the theaters to see them.

“There was a time when I read something (about a Perry film) and I wanted to cry,” he said. “I thought to myself, does this person understand that my mom, who is 70 years old, and all of her friends, they leave church and go to the theater on Sunday evening and they pay their money and they absolutely love that film. You know why? It’s speaking to them,” he said. “Art is art and sometimes you have to step back if you’re not breathing that same air.”