ATLANTA (AP) — Stacey Abrams spent years crisscrossing Georgia, working to convince Democratic leaders, donors and prospective candidates that a vast, untapped well of potential voters could upend Republican domination in the state. There was no national media spotlight or constant praise from national political players to ease the slog.

That’s over now.

After disappointments including her own narrow defeat for governor in 2018, Abrams is being credited with laying the organizational groundwork that helped Democrats capture the state’s two Senate seats. Those victories this week propelled the party into the Senate majority and follow Joe Biden’s win in November, the first time a Democratic presidential candidate has taken the state since 1992.

The turnabout leaves Abrams as perhaps the nation’s most popular, influential Democrat not in elected office. It gives the 47-year-old voting rights advocate considerable momentum for whatever comes next — most likely a rematch with Gov. Brian Kemp in 2022.

“I think what’s next for Stacey is whatever Stacey wants to be next,” said Leah Daughtry, a former chief of staff at the Democratic National Committee. “She’s clearly demonstrated her political prowess, her ability to plan — Georgia didn’t happen overnight.”

Democratic Governors Association Executive Director Noam Lee previewed the potential matchup in a brief statement: “Gov. Kemp, you’re next. See you in 2022.”

Former President Barack Obama called Georgia “a testament to the tireless and often unheralded work of grassroots organizing” and credited Abrams with “resilient, visionary leadership.”

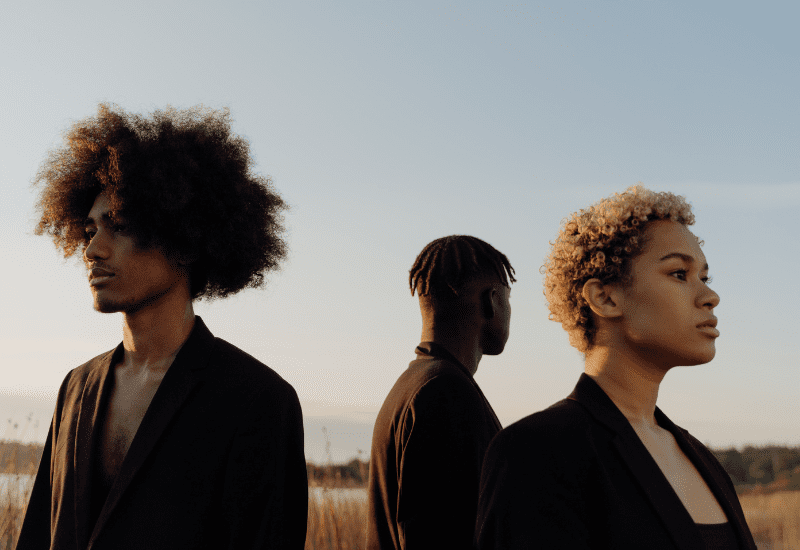

The praise came fast and furious, especially from her fellow Black women who, collectively, saw their stock rise in Democratic politics in 2020 after spending decades as an underappreciated anchor of the party. “Stacey Abrams (that’s the tweet),” wrote Karine Jean-Pierre, incoming deputy White House press secretary.

“She’s earned her spot as a party elder and a party wise-woman,” said Karen Finney, one of Abrams’ advisers in her 2018 campaign.

Former Democratic National Committee Chair Howard Dean called her the “LeBron James of American politics.”

“She has just an enormous amount of talent, and the ability to focus that talent in a very intense way,” Dean said. “And so when you get somebody like that, of course you want them elevated as much as possible.”

On Monday, Abrams had stood at Democrats’ election-eve rally where Biden gushed that “nobody in America has done more” for voting rights and the party.

“Stacey, you’re changing Georgia,” Biden said. “You’ve changed America.”

Abrams, a Mississippi native with degrees from historically Black Spelman College and Yale Law School, attempted to deflect.

“Let’s celebrate the extraordinary organizers, volunteers, canvassers and tireless groups that haven’t stopped going since November,” Abrams tweeted as the Rev. Raphael Warnock’s victory became apparent. “Across our state, we roared. A few miles to go … but well done!”

But Georgia’s shift in 2020 is a reflection of her willingness to see a new coalition in Democratic politics — and to fight even her party’s old guard in the process.

“This is a lot of work, but people need to believe in building multiracial, multigenerational, geographically diverse coalitions — and that means believe in Black people in the South,” said Lauren Groh-Wargo, who managed Abrams’ 2018 campaign for governor and now leads her Fair Fight Action political organization.

“For years, that just wasn’t a thing,” Groh-Wargo continued. “People told us year after year, no, Black people don’t vote in the South and white people are too hard.”

Essentially, Abrams was telling the mostly white, older power brokers in Georgia Democratic politics that they were on a fool’s errand trying to convince older white voters to return to the party after decades of a Southern shift toward Republicans. The path to closing the gap with Republicans, she insisted, was drawing new voters to the polls. In her vision, that would include everyone from transplants to metro Atlanta to older Black voters who just didn’t vote and younger white Georgia natives who simply aren’t as conservative as their parents and grandparents.

It almost worked in 2018.

Abrams won the Democratic nomination over a fellow state legislator recruited by the party’s white power brokers who weren’t convinced a Black woman could win in Georgia. In the general election, she finished less than 20,000 votes shy of forcing a runoff against Kemp, a small fraction of the usual Democratic shortfall of 200,000-plus votes. She turned her loss, and her insistence that Kemp had used his post as secretary of state to make it harder for Georgians to vote, to double down.

Transitioning her campaign into Fair Fight, the group continued registering tens of thousands of Georgians. The close loss drew in plenty of money, including a seven-figure investment from billionaire Michael Bloomberg. Other groups followed, seeing Georgia as fertile ground for Democratic organizing.

Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer more or less openly begged Abrams to run for the Senate in 2020 — at the same time some supporters urged her to run for the presidency. She demurred, continuing her work in Georgia and expanding Fair Fight into 19 other battleground states. According to Democrats with knowledge of their conversations, it was Abrams who helped persuade Warnock to run.

At the same time, Abrams never stopped pushing Democrats to support her Georgia efforts and copy them nationally.

“Any decision less than full investment in Georgia would amount to strategic malpractice,” Abrams and Groh-Wargo wrote in a 2019 memo sent to presidential candidates, Democratic National Committee leaders and top party strategists and pollsters. They wrote that Abrams’ 2018 coalition of nonwhites and whites from the cities and suburbs was a blueprint “to compete in the changing landscape of the Sun Belt.”

It was a national replay of the same tussle she’d had years before with Georgia power players, as she argued for an expanded electorate rather than chasing former Democrats and GOP-leaning independents.

Groh-Wargo emphasized this week that one difference between 2018 and 2020 was the success at turning out Black voters in rural areas. “This is the model for states like Mississippi and Alabama … even Ohio,” she said.

Abrams was among the 11 women whom Biden interviewed for his running mate, a process that led to Kamala Harris being the first Black woman nominated and elected to that office. While Abrams did not make Biden’s final “short list,” she again managed to rewrite some of the rules.

While some contenders, including Harris, sidestepped questions about being considered, Abrams was unapologetic about the possibility.

“The issue of being able to serve as lieutenant and possibly to step in is a question of competence, (and) I would put my resume against anyone else’s,” she told The Associated Press in May.

Days later, she explained her self-assurance on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

“As a young Black girl growing up in Mississippi,” Abrams said. “I learned that if I didn’t speak up for myself, no one else would.”