“The universe thinks and responds to your thinking, and this is the essence of what Hip Hop is for us; it is our relationship with divinity. Hip Hop is what we are doing with our portion of GOD.” KRS-One

On April 16th, 2025, Mass Appeal announced the launch of the ‘Legend Has It’ series: a procession of albums curated from seven of New York’s most highly regarded stalwarts, to be released by the label in monthly succession. This series would mark the grand return of storytelling rap forefather Slick Rick after a 25-year absence; the resurgence of Wu-Tang Clan lead member Raekwon; the reinvigoration of rap music’s very own Iron Man, Ghostface Killah; the divinely inspired final offering from Mobb Deep; the posthumously peerless resurrection of Big L; and the emotionally charged, melancholic, but ultimately optimistic opines of De La Soul. All of these albums are quality listens, with each artist doing what they do best at the highest levels of lyrical craft and sonic vision.

But there was one final album to be released; an album that famously (or infamously) stood as a Holy Grail within the pantheon of the so-called “Hip Hop Head’s” mantle of dreams. An album whose lore bordered on a mythology fit for King Arthur’s roundtable, with the stoking fires of its possible existence dating back twenty years to a now-defunct magazine’s cover article. An album started and stopped, teased and dismissed, promised and disavowed, perhaps more so than any Hip Hop album not named Detox: the Nas/DJ Premier collab album.

In 2022, at the artistic peak of what would become his six-album tour de force with Californian super-producer Hit-Boy, Nas—on the song “30” from King’s Disease 3—slyly let it slip that the “Premier album still might happen,” putting fans and the hip-hop world at large on notice that he was very much aware of what they wanted. He spent the next year putting the finishing touches on his Hit-Boy era, releasing two more albums before quietly spending 2024 conceptualizing and strategizing the ‘Legend Has It’ series. With the announcement of the series, Nas spent the majority of 2025 unleashing a volley of feature verses so potent in their delivery and epochal in their execution that, even had he failed to deliver an album, he would still be in serious contention for the year’s rap MVP.

There was the scene-stealing verse on Slick Rick’s “Documents,” where Nas essentially tells a story about becoming one of rap’s most celebrated storytellers. Then there was his feature on Ghostface’s “Love Me Anymore,” where he admonishes friends-turned-haters embittered by their failure to take advantage of the opportunities he gave them. There was the ferocity and viciousness of his turn on Big L’s “U Ain’t Gotta Chance,” where he dismissively brushes off the challenges of lesser rappers, and the more buoyant showing on De La’s “Run it Back,” where Nas imagines himself as the group’s fourth member (as well as that of the Bee Gees, ZZ Top, and The Fugees). Similarly excellent verses on Raekwon’s “The Omerta” and three songs on Mobb Deep’s Infinite LP culminated in a feverish anticipation for a new Nas album.

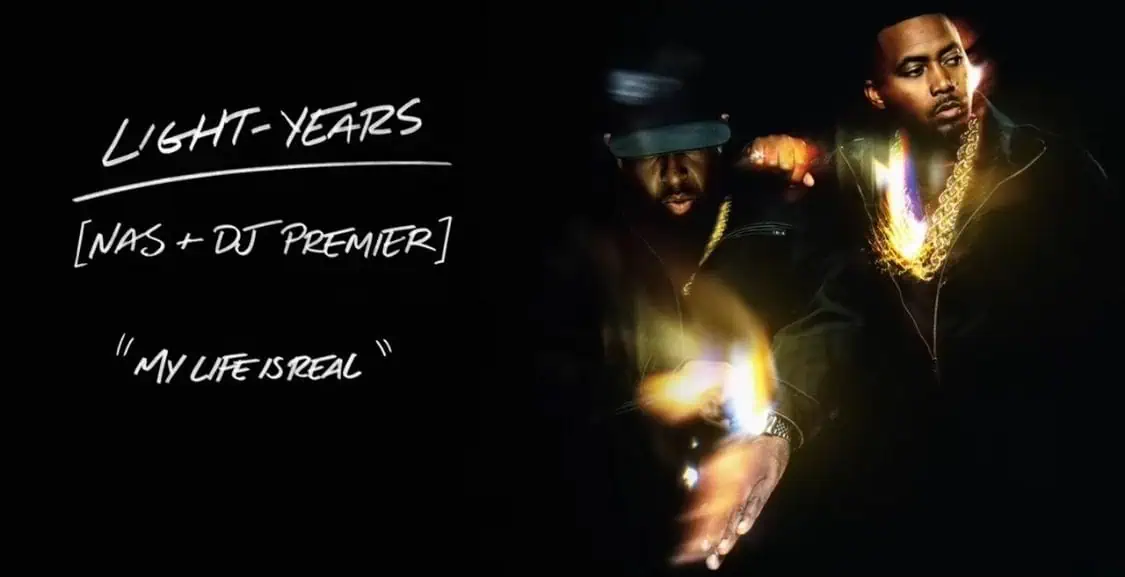

And finally, on December 12th, almost 24 years since Premier graced his iconic scratches on a Nas album, it was delivered: Light-Years, 15 tracks of raw, unfiltered beats and rhymes presented by none other than the men born Christopher Martin and Nasir Jones. Myth had finally become reality as the clock struck midnight and the opening piano keys of intro “My Life Is Real” blared across smartphones, car speakers, and stereo systems across the world. Nas opens this song confidently reinterpolating lyrics from his 1996 It Was Written album cut “Live Nigga Rap,” updating his swagger and acuity in self-assured proclamation: “Wavy hair, mystique / up in this bitch deep / Chain with some sick feet / corner of 10th street / Scoop me in the MPV / I’m holdin’ big heat / Soloist vocalist, maestro / this fish grease.”

On the song’s second verse, Nas boldly trumpets the new album as a classic—a term he is overly and overtly familiar with, as his storied discography contains a multitude of them. It is a testament to Nas & Premier’s chemistry that the production and lyrics feel seamless. Premier’s beats are minimalist in execution, allowing Nas the space to tell stories, edutain, and just talk his shit. The second track, “Git Ready,” is a perfect example of the latter as Nas flexes his wildly publicized investment achievements in both tech and Coinbase: “Serial investors, serial killer threat / Turn Ether to Ethereum, y’all wanna bet? / I got a crypto key, it come with a password / Then I flipped that key to digital cash, word / But then I get bored of that, it’s too small, I’m off of that / Cigars in the roof now, midtown, where the office at.”

Things take a turn for the bold on the third track, “N.Y. State of Mind Part 3.” Instead of the familiar piano sampling of Joe Chambers’ “Mind Rain” that accompanied the previous two versions, Nas & Premier chose to incorporate Billy Joel’s 1976 original, creating a harsh but ultimately hopeful amalgam between Joel’s fairy tale and Nas’s reality: “Stress’ll cut your life short, I’m from egg rolls and duck sauce / Where the feds rolled on Dutch Schultz, City Island, and Sei Less / Plenty talent, the kids stay blessed, gamble and make bets / Throw on some DMX, his words, they live in all of us / Some get deported, some die young, but it’s all a rush / On part two, I left you with two of my friends / And now our goals is that our sons don’t end in juvenile pens / Rikers should be closed, MDC to Beacon / Wear ice if you real, or they’ll rob you and pawn your piece in / If you was locked down for a while, it’s a different place now.”

It’s an attestation to Nas and Premier’s creative vision that, instead of giving fans the sonics they’d expect from an entry into the “NY State” series, they chose to go with a less aggressive, rugged beat—opting for something orchestral yet grainy, akin to a score from an early Spike Lee joint. As the song ends, we get the familiar “Flight Time” monotone chirps sampled from Donald Byrd, a sort of farewell nod to the legacy of the original, as Nas & Premier have confirmed that Part 3 marks the capstone of the series. This also concludes the “here & now” portion of the album, as the fourth track, “Welcome to The Underground,” kicks off a new chapter: the celebration of hip-hop’s origins and a dedication to the four elements. Starting with an intro from rap video icon Ralph McDaniels and featuring a scratched hook from Ice Cube, Nas rejects the glitz, glimmer, Grammy-pandering, and anything associated with mainstream pop appeal. He wants to take the listener back to 1986—a year that saw the debut of luminaries Salt-N-Pepa, 2 Live Crew, and Beastie Boys, and also the year Run-DMC became rap’s first superstars with their Raising Hell album. Nas boasts that even without fancy equipment or a studio, he and Preme can make magic beatboxing and banging on tables.

The ode to the good-ole-days continues on the fifth track, “Madman.” Over a sinisterly affecting beat, Nas eulogizes Sacha Jenkins (whose early-‘90s hip-hop focused magazine Ego Trippin’ was the first publication to feature Nas as a cover story), reminds us that he was the first to start the trend of artists recruiting super-producers together for one project, and affirms his relevance predates that of contemporaries Wu-Tang Clan and The Notorious B.I.G.

The sixth track, “Pause Tapes,” is a lesson in early-‘80s production and beat-making. Nas takes us back in time to when he was a young teenager living in Queensbridge Housing Projects and dreaming of being a rapper. Here he meticulously lays out how he and hundreds of kids without access to MPC workstations utilized the tools at hand, demonstrating how the combination of youth, ambition, and African-American ingenuity gave rise to a sound that would, in the not-too-distant future, define a generation: “Pickin’ up the stereo’s remote control, quickly / Ron G’s in the cassette deck, rockin’ the shit, G / A surprise – I opened up, bombshell in my mind / Tells me I could hook a beat up for myself to rhyme / My mom’s hall closet, in boxes, all kinda shit / Johnnie Taylor records and some good Grover Washingtons, I’m lockin’ in / Grab a piece of vinyl, drop the needle at the top / Listen for a beat to rock, 90 minute tape, I got enough time / Play it one time, four bars / Press Record, then press Pause, then restart / Record, loop, repeat / Do that ’bout twenty times – yo, I made my first beat / Pause tapes!”

The story of hip-hop’s most overlooked element, graffiti writing, is given its flowers on the seventh track, “Writers.” Over a mystical and drum-laden production (heavy with Premo’s signature scratches), Nas waxes poetic about his profound admiration for graffiti’s greatest bombers, shouting out unheralded names such as Dondi, Ecko, Totem, and Tracy 168, as well as better-known legends such as Dez (AKA Kay Slay), Lee Quiñones, and the immortal Samo (Jean-Michel Basquiat).

The eighth track, “Sons (Young Kings),” serves as a companion piece to the 2012 single “Daughters” and is one of Nas’s more personal and heartfelt performances on the album. On the first verse, Nas talks about the precarious balance a father faces in attempting to both parent and guide a young son—too much direction can become micromanagement, whilst too little can lead to incompetence. Nas runs down a list of advice he wants to impart before surmising that a focus on health, both mental and physical, is the most important tip he can voice. The second verse flashes back to Nas’s own childhood as he reminisces about life with his mother and how her protection allowed his whimsical fantasies and musings to flourish: “Plenty stuff I used to see I often thought was an image of us / Getting off the city bus, all the memories rush / I used to look up at the crossing sign / A child with a grown-up hold in his arm while I was walking with my mom / I pointed at it, automatic / I saw it as a little boy who was the baddest / Like don’t let him run in traffic / I really thought the crossing sign was me and my mom / Like who thought we was that important for a street sign / One year, she told me that sign was for everybody / I’m like, ‘We ain’t everybody, nah, we special, Mommy.’”

The visual illustrated here is exemplary of the why and how of Nas as hip-hop’s greatest writer. The ability to capture a child’s naivete as it pertains to himself and his place in the world – a world far bigger than the crosswalk on which he and his mother stand, yet narrow to the point where he sees himself at the center of it – is a skill unmatched by anyone before or since.

The dedication to craft and skill continues with the ninth track, “It’s Time,” where Premier samples the classic Steve Miller Band hit “Fly Like an Eagle.” Here Nas weaves in and out of the beat with a lyrical dexterity that defies time itself. From his voice to his flow, it’s hard to tell the 52-year-old mogul apart from the 17-year-old wunderkind who burst forth in spectacular fashion on 1991’s “Live at The Barbecue.” Nas may no longer be snuffing religious figures or kidnapping heads of state (with or without a plan), but his sense of cadence and timing remains pristine.

Track 10, “Nasty Esco Nasir,” is a treat for fans of Nas’s creative writing experiments in the vein of “Rewind,” “Book of Rhymes,” and “Project Roach.” Nas inhabits his two most famous alter egos: the “Nasty Nas” that won him acclamation and a claim to hip-hop’s ever-competitive “King of New York” mantle, and that of “Nas Escobar,” the doppelganger that afforded him world-wide fame, fortune, and a place as one of the genre’s superstars. Over eerie strings and a thumping bass, Nas uses three distinct flows and vocal inflections to essentially battle himself. But when Nasty and Esco can’t come to terms and end up (spoiler alert) killing one another, it is Nasir Jones—the man who at once embodies both of them and neither of them—who rises from the proverbial ashes: “I’m a father, philanthropist, film director, an author / Tech impresario, Resorts World casino partner / A restauranteur, by the time you hear this song / I’ll probably open up a whole new store, get involved / I’m a mogul, massive with my moves, everything got appeal / I lead the way, I’m tryna see much more of us here / Even make our own cigars top tier / We do branding, expanding a thirty-year career / I’m just scratching the surface, the next phase of Nasir / Phase four, the fourth dimension, the legacy’s here / And other things I won’t mention, I’m winnin’ when I’m not even trendin’ / Trailblazin’, the message I’m sendin’ / When you evolve into your true growth, they say you can’t do both / Feed your soul and get money, I’m like two GOATs.”

Track 11, “My Story, Your Story,” marks the official reunion of one of rap’s most celebrated duos. Nas and Brooklyn wordsmith AZ team up for the first time since 2002’s Grammy-nominated single “The Essence” to remind everyone that their musical chemistry remains unmatched. As they go back-to-back, verse for verse, finishing each other’s lines like twin brothers connected as much by spirit as by blood, one can only hope that Nas’s fan-service era extends just a little longer to gifting us the long-asked-for Nas/AZ project.

Track 12, “Bouquet (To the Ladies),” makes use of a beautifully lush Eugene Record “Here Comes the Sun” sample, with Nas paying homage to almost every female MC of note across rap’s 50-year history (seriously, he raps about or shouts out over fifty female rappers), with a special nod going to Faith Newman, the Columbia Records executive who signed him when he was 18.

Track 13, “Junkie,” is another conceptual song where Nas utilizes the analogy of a drug addict to describe his addiction to rap music and inability to quit rhyming. One hopes Nas never kicks the habit, as again his lyrics and flow meld with such deftness to Premier’s hulking bass and ghostly strings that it is as if his voice is an instrument itself, bringing life to what the beat is attempting to convey: “Bruh, I’m suppose to been kick this habit / Done with it, havin’ fun with it / Hard to let it go, how could you when you in love with it? / Once upon a time, I couldn’t start my day without it / I played it every morning loud while I’m ironing my outfit / In my car just zonin’ out, straight hot-boxin’ / I need that real dope, I cannot fuck with Suboxone / Medications, they just don’t work, my body jerks.”

The penultimate track, “Shine Together,” sonically is probably the most reminiscent of past Nas/DJ Premier collaborations, with a cheery, bouncy sample of Sunbear’s “Let Love Flow for Peace” evoking cognizance of “Nas is Like.” Here Nas celebrates his and Premier’s longevity, reflecting on lessons learned and basking in the renown they’ve both earned from tireless work and dedication to the craft. On the last verse Nas spits: “This is my dissertation, displayin’ it at my leisure / Precious like postal cards written by slaves in secret / Black preachers castin’ spirits back into Hell / Hear the trumpets in the Bible as Joshua starts to yell / Easy money is robbery in broad day / Might call BET to play my videos all day / The cribs are mini-museums / The closets are more like small department stores / I drop that raw.” His are the words of a man who’s seen it all: war, death, joy, pain, triumph. And he delivers his message with a sense of biblical importance, not as a display of ego, but as a memorandum of hope. The hope that a kid from America’s largest housing projects can serve as the voice of a generation. The hope that aspiring artists can reach the same heights. The hope that black brilliance can be utilized as a stepping stone for black liberation (both economical and environmental). The hope that black voices continue to echo throughout time, in both song and rhyme.

Track 15, “3rd Childhood,” is a pseudo-sequel to 2001’s standout “2nd Childhood.” On the latter track, Nas muses on the endemic of immaturity that keeps young black men and women of the ghetto entrenched in a never-ending cycle of self-destructive Peter Pan syndrome. On “3rd Childhood,” Nas contemplates the inherent hypocrisy in admonishing rappers to “grow up, stand up, and clean up” when rock and pop stars are allowed to be “rebels” well into their middle years: “Is it time to take off the scully, the Timbs, and the fitted caps? / Time to let go of the weed, can’t let the jeans sag? / Ozzy Osbourne still got his fingernails black / Rock and rollers still rebels, any age that they at / But with rap, it’s a time limit? Never / I’m livin’ proof, I’m the truth ’til if I live a-hundred-and-two / When I was young, I knew nothing, but then here comes a new lesson / From a older gentlemen dressed in Dior, he flexin’ / He said, ‘It’s not how old you are, it’s how you feel’ / Look here, I’m in my Air Max ’87 still / Rastas still smokin’, secluded out in the bush / Pimps still wearin’ their derbies, people still dippin’ snuff / That’s how it stay true, ways we learn in the days of our youth / Seen a man, like eighty-two, he rocked his hat ace deuce / I’m goin’ out hood, different from bein’ a third childhood / Switched it up a little, but still, I’m goin’ out hood.”

Nas refuses to allow society, which historically has berated hip-hop as unworthy of being sanctioned as art, to dictate the terms of what is appropriate behavior for the genre’s representatives. Rather, he leaves that to the culture itself, for the culture has always self-corrected, self-administered, and self-made any and all salves for its continued success and development. And here is where Nas and DJ Premier’s genius lays within the context of the album. They didn’t set out to “save” hip-hop. They didn’t set out to outdo their previous works. They didn’t even set out to make a classic. The mission of the album was to uplift that which needed upliftment, celebrate that which needed celebration, and shine a light on that which needed illumination: the living, beating heart of hip-hop itself. They chose to take their portion of God and praise Him for all that He is, all that He isn’t, and all that He will be.

According to NASA, a light-year is meant to describe a unit of length (distance) to stars and other galactic entities; it is not meant to describe or define a unit of time. When Nas chose the album title, he was trying to convey hip-hop’s distance from other genres or art movements. This is a distance measured in prophetic terms, as hip-hop has been so far ahead in its influence that its cultural relevance outpaces any artform nameable (there’s a reason why Jay-Z, in 2009, could boast that he’s a “small part of the reason why the President is black” and no one batted an eye). Time is undefeated, you can’t outrun it, out-think it, or out-gun it; it’s coming for us all. But Nas isn’t afraid of time; he embraces it like a friend. For time proves all theories either right or wrong, and Nas’s assertion that hip-hop will continue to evolve and thrive, continue to distinguish and distance itself from anything past, present, or future, is as prophetic as anything Nostradamus or Edgar Cayce could dream up. For he told us back in 1994, when he was that fresh-faced prodigious poet standing on the precipice of changing the world: “Time is Illmatic.” Or so legend has it.

SCORE

Lyrics – 5/5

Production – 4.5/5

Overall – 4.5/5

👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾🔥🔥🔥🔥