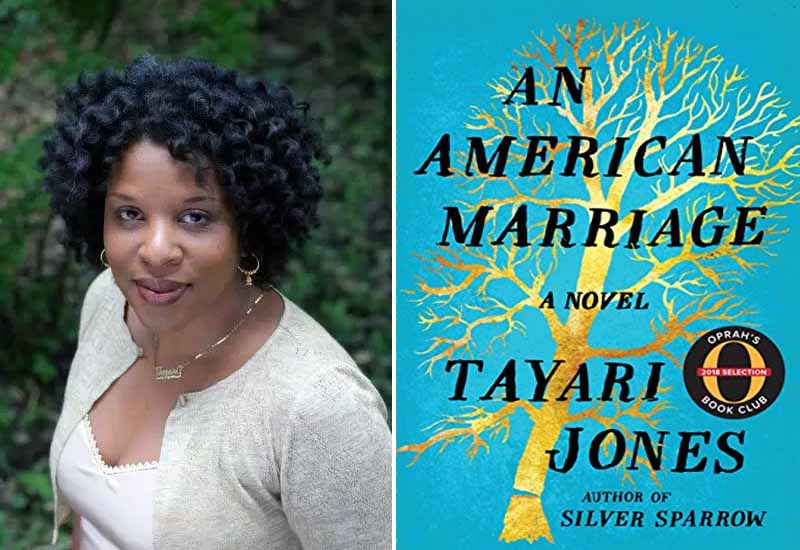

I first met Tayari Jones through her novel The Untelling. I was applying to graduate school for my MFA in Creative Writing and after reading her novels, I knew I wanted to work with her. You can imagine my delight when upon submitting my application to Rutgers, I received a phone call from her personally congratulating me on my admittance into the program.

Tayari always encouraged my peers and me to dial up the drama, to write wild, and edit later. In her own turn of phrase, she likened this strategy to running a bath. “Turn the hot water, all the way up. Then you can go back and slowly cool it down.”

While I graduated seven years ago, I continued to support her work, gobbling her narratives almost as quickly as the books hit my hands. You can imagine my happiness and pride when I heard the news that her latest work, An American Marriage, was selected for Oprah’s book club. Despite traveling the world, doing interviews, and book signings, Tayari spoke with us here at Jaro. Her willingness to carve out time from her hectic schedule speaks volumes about her character as a teacher, mentor, and writer. We cannot even begin to express our gratitude for her generosity.

In conversation, we spoke with Jones about her latest novel, An American Marriage, to discover more about the beautifully complex characters that inhabit the pages, the triumphs and pitfalls of writing, and the immeasurable fascination behind entangled relationships and the family dynamic.

What are some of the most interesting fan responses that you have been receiving about An American Marriage?

The most interesting thing is that I thought that I would be hearing a lot of things from women who have husbands incarcerated, but actually, mostly I’m hearing from mothers who have incarcerated sons. It’s kind of a side plot to the novel, but it has resonated so much with the mothers. That surprised me; it wasn’t what I was expecting. I’ve also been very surprised at how many people see themselves in the characters for other reasons. I’ve met people who say, “Oh, my husband is in the military. He’s away,” or, “My husband is working in Singapore.” Even though I felt like I wrote the story in a very specific way, it is resonating with people who have other experiences.

You say you try to empathize with the characters. Was there a character in particular where it was hard to inhabit their particular point of view, or you had difficulty inhabiting their point of view?

I always start from a place where I feel like if I don’t like a character, I can’t spend enough time with them to put them in my book. You have to spend all this time thinking about these people and going through their experiences with them. I always come at them from an open-hearted space.

Some of their experiences are different than mine, and they took more imagination for me to inhabit them, but I wasn’t forcing myself to identify with them.

Is there a character that took more of your imagination to inhabit?

Roy’s mother. I don’t have children, and so I had to really think about what it would be like to feel responsible for another human being to be in the world. I had to imagine and think about that.

You tell people that it’s okay to not have a lot of time to write. In fact, people who are the busiest probably have the most stories to tell. What are some of your practices for writing? Do you have a flow, a process?

When the writing is going well, when I have lots of ideas, I feel really energized. I could write anytime when it’s working. It’s like being in love. When you’re in love, you find the time. No one ever says, “I’m madly in love, but I just don’t have the time to participate in this relationship.” You start having trouble finding time for the relationship when the relationship isn’t going that well. So when the writing’s good, I have no trouble with my rituals. I love to get up early. I clean the desk before I go to bed so that when I wake up, the desk is clean and I’m ready. I look forward to it. But when the writing’s not going well, that’s when I have to become more disciplined. I set a timer, and I sit there and I can’t get up until the hour is over, even if I write nothing. I do find that if you promise yourself that you’ll sit for an hour, you will write something. So over the six years, there were ups and there were downs. My practices really vary depending on the amount of enthusiasm I have.

You’ve previously explained the story of how your inspiration came for Celestial and Roy, but what was your inspiration behind the other characters, such as the four fathers from completely different worlds?

Once I start with a character, the process of writing them, I just imagine the other people around. I just say, okay, this is how Roy is. Who are his people? How did he get there? I just imagine how such a man comes to be. I do think that writing fiction is a little mysterious and a little magical because you are creating things out of thin air. In real life, I could overhear a conversation, and it will ignite my imagination. For me, the pleasure in writing fiction is how much I just get to run with it in my own head, without having to be beholden to actual people or events.

I don’t like to write non-fiction for this very reason. If you’re a fiction writer, it’s very hard to write non-fiction because as a fiction writer, you think – I know how I can fix this story. But when you’re writing non-fiction, you have to report. You’re not allowed to shape it in the same kind of way you can in fiction.

All of your novels deal with complex family structures. Do you find something particularly fascinating about exploring family dynamics versus friendships, for example?

The family is the original entanglement, and there’s so much possibility for story there because family is the relationship where you can’t really opt out of it. You can’t quit your mother; you can’t quit your father. You can, but they’ll still be your parents. If you divorce your husband, he’s no longer your husband. You could divorce your mother, but she’s still your mother. So that already gives you a certain narrative, the permanence of that relationship. That already makes it more tense, and gives you so much more room. It’s perfectly right for storytelling.

The only stories that are interesting are complicated stories. For love stories, if a relationship is going well, it’s only interesting to the people in it. It’s when a relationship isn’t going well that other people want to know what happened. No one wants to be like, “Tell me more about how you all have dinner together every night and say nice things to each other.” No one wants to know that because it’s not interesting. It is conflict that makes stories interesting.

In another interview, you spoke about how you usually write towards a question. What were some of the questions that you were writing your way through in this novel?

The question that I really had in this novel was how does a woman artist, in Celestial’s case, try to balance her own desires, dreams, and aspirations, with that of their partner? And her husband is coming up against a racist institution. How, then, is her sacrifice, or lack of sacrifice to him, does he become a proxy for a question of justice? If she does not remain in the marriage in the way that he wants her to, then is she not supporting the race? Is that fair, is that reasonable?

What was the most fulfilling part of writing An American Marriage? The most difficult?

I had so much fun with the letters, because I write letters in real life. I also enjoyed the humor in the book. I feel like all the fathers in the book, they all think they’re funny. The most difficult was to work out the ending. I felt like I had the people in such a complex situation that I did not know how to unravel it. I felt like they had suffered so much; I wanted to give them all something, a gift. That was really hard to figure out how to do it.

Did you just write your way through it, or was there something that helped you to figure out how to write the ending?

I just kept trying different things. I kept thinking about it, kept ruminating on it. I realized that the question that I thought the novel was about, which was whether or not Roy could regain the things he’s lost. But I realized that what he really lost was an emotional thing, which was empathy. Therefore, when I figured out how to give him empathy, I figured out how to end the book.

In what areas do you think that An American Marriage has aided in your growth as a writer?

This is the first novel that I’ve written that didn’t have any young characters. It was the first time that I had to write a novel and I had to ask questions that I don’t know the answers to, in a different kind of way. With young characters, as an adult, you know things that they don’t know. So it’s easier to control the story because you’re just wiser than they are. You always have to know more than your characters, and so the characters in An American Marriage were so much closer to my own age and the questions they were asking were the kinds of questions that I’m asking in my own life. It was harder to maneuver.

What are you reading right now?

A lot of my students that I’ve taught in various capacities are publishing novels and it’s very exciting, such as Margaret Wilkerson Sexton’s A Kind of Freedom. I really am quite taken with it. Having seen it as a draft in class, it’s really a thrill to see how it blossomed and became long-listed for the National Book Award.

For aspiring authors, what advice would you offer to those who struggle with finding the motivation and confidence to keep on writing?

The main thing is to surround yourself with others who are writing so that it feels normal. When you see other people writing, you know you can do it, too. I think that’s really important. When you’re all alone doing it, you just feel like, “What am I doing, and why, and how?” and it just feels insurmountable. Find writing communities that you can be in, take classes. Do things to keep the project alive and part of your life.

To learn more about Tayari Jones and her work, please visit her website.