SELMA, Ala. (AP) — John Lewis saw the line of Alabama state troopers a few hundred yards away as he led hundreds of marchers to the apex of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on March 7, 1965. Armed with gas canisters and nightsticks, the troopers were flanked by horse-riding members of the sheriff’s posse. A crowd of whites milled around nearby.

Lewis, who died Friday at age 80, was just 25 at the time. He had been leading voting rights demonstrations for months in the notoriously racist town, and he and the others were trying to take a message of freedom to segregationist Gov. George C. Wallace in Montgomery.

So, rather than stopping, Lewis put another foot forward.

That seminal step propelled him on to a global stage as a hero of the U.S. civil rights movement. The ensuing confrontation helped lead to the passage of the federal Voting Rights Act.

With fellow civil rights activist Hosea Williams at his side, Lewis finally stopped a few feet away from the phalanx of troopers commanded by Maj. John Cloud of the Alabama Department of Public Safety. Other marchers stopped behind them, shifting their feet uncomfortably on the bridge shoulder.

Williams asked Cloud whether they could talk. There would be none of that, said Cloud. Acting on Wallace’s order, he said the march was illegal and gave the group two minutes to leave. Seconds later, Cloud unleashed a spasm of state-sanctioned violence that shocked the nation for its sheer brutality.

“Troopers, here, advance toward the group. See that they disperse,” he said through a bullhorn. Lewis stood motionless with his hands in the pockets of his raincoat, a knapsack on his back.

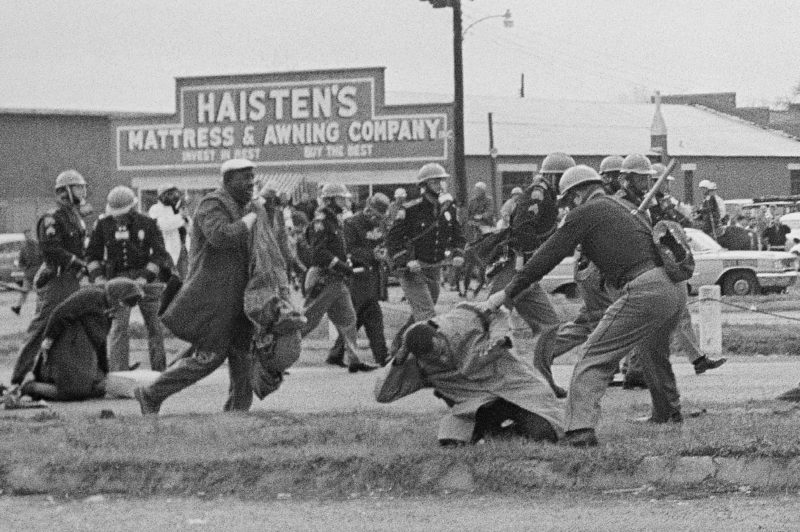

Archival film footage and photos show a line of roughly two dozen troopers wearing gas masks as they approach the long, peaceful line led by Lewis. A trooper jabbed the butt of a nightstick toward Lewis and officers quickly pushed into the group. Feet became tangled and bodies hit both the grass roadside and the asphalt road. Screams rang out.

Lewis, in sworn court testimony five days later before U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr., recalled being knocked to the ground. A state trooper standing upright hit him once in the head with a nightstick; Lewis shielded his head with a hand. The trooper hit Lewis again as he tried to get up. The officer was never publicly identified; Lewis testified he didn’t know who it was, and a gas mask shielded the man’s identity.

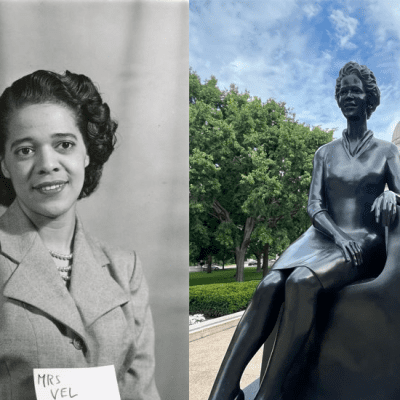

Others were beaten even worse as whites cheered from nearby. Amelia Boynton Robinson, who was in the line behind Lewis, was tear-gassed and beaten so badly she had to be carried away unconscious. Others were clubbed by the sheriff’s posse members on horseback.

Lewis testified he never lost consciousness, but he also didn’t remember how he got back to a church where he was taken before being admitted to a hospital. He got out in time for a hearing before Johnson, who overturned Wallace’s order and ruled demonstrators could march to Montgomery.

Lewis was just a few feet away from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the front of more than 3,000 marchers when they left Selma on March 21, 1965, for the epic 52-mile walk to Montgomery. Wallace, who had vowed “segregation forever” during his 1963 inaugural and served four terms as governor, refused to meet with them.

Lewis outlived other key players in what came to be known as Bloody Sunday by many years. He addressed a throng atop the bridge in March, after his cancer diagnosis, to mark the 55th commemoration of the day.

“Speak up, speak out, get in the way,” said Lewis, who appeared frail but spoke in a strong voice. “Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.”

Wallace died in 1998, five years after Cloud, and Judge Johnson died in 1999. Hosea Williams, the other march leader who was beside Lewis that day on the bridge, died in 2000.

Robinson, who recovered from her injuries and crossed the Selma bridge with Lewis and then-President Barack Obama during the 50th anniversary commemoration, died in 2015.