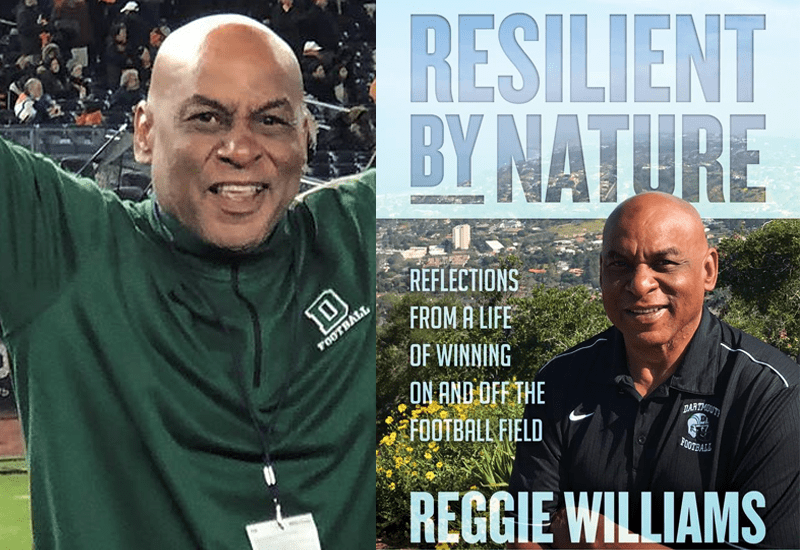

If there is a “resilience continuum” measuring from low-to-high a person’s ability to recover quickly after a setback, former National Football League player Reggie Williams would be off the scale. In his award-winning memoir, Resilient by Nature: Reflections from a Life of Winning On and Off the Football Field (Post Hill Press), the Flint, Michigan native Williams along with USA Today NFL columnist Jarrett Bell tell a remarkable life story of the gridiron great who overcame obstacles throughout his lifetime, experienced tremendous success as a sports executive as well as became a civic leader and social justice innovator who created opportunities for others.

Learning how to succeed over difficult circumstances early in life helped shape Williams’ character and that experience allowed him to turn adversity into opportunity for himself and others. A profound hearing disorder took him to the Flint-based Michigan School for the deaf as a child. His hearing condition was corrected after two surgeries. That experience led him to help others when his professional football career ended.

A concussion as a freshman high school football player was the harbinger of future and on-field injuries he had to overcome. Being rejected in person by legendary University of Michigan coach Bo Schembechler who told him “He wasn’t good enough” was another setback and it opened the door to a Dartmouth College academic scholarship where he became a three-time All-Ivy League linebacker and in his senior year earned First Team All-American honors as the last Ivy League player to ever gain major college All-America status.

Praise did not come without pain for Williams during his 14 seasons in National Football League with the Cincinnati Bengals. The hard-hitting linebacker’s regular season play and two Super Bowl appearances produced numerous accolades for on-field performance such as being named to the 1976 NFL All-Rookie Team and the Sports Illustrated issue Sportsmen of the Year in 1987. His off-field commitment to community service earned him the Byron “Whizzer” White Award for Humanitarian Service in 1985 and the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year in 1986.

In line with serving others, he was appointed to an open seat on the Cincinnati City Council in 1987 and re-elected for a second term the next year. However, during his career there were three more concussions and a series of knee injuries from playing on hard-as-rock artificial surfaces that led to 28 surgeries for pain relief and posture leaving his right leg three inches shorter than the left one when he retired. Along with the string of surgeries came countless recommendations by doctors for him to amputate his right leg. Finally, a novel three-inch platform walking shoe allowed Williams to walk without a cane or crutches. Again, the strength of his character forged earlier in life helped him push through adversity. After the NFL, Williams became a sports executive managing the fledgling World League of American Football and the New Jersey Knights.

Williams credits his parents as well as Thurgood Marshall, one of his heroes that he began reading about from an early age, for developing his social consciousness. Reading had been offered to him as a consequence of his hearing impairment. Williams is the type of person who sees something that should happen and gets it done. The National Football League was considering some type of philanthropic effort in connection with the Super Bowl XXVII in 1993. However, the league did not have concrete plans. In a true-to-form bold example of innovative social justice and action, Williams prepared a comprehensive plan for Youth Education Town, a multi-purpose education and recreation center in South Central Los Angeles. While this part of the city is known infamously for gang violence, Williams knew it was a community composed of mothers, fathers and children that are all part of families that deserved respect.

With the help of Garth Brooks, Disney and National Football League support, Youth Education Town opened around Super Bowl XXVII in Pasadena a short distance from South Central Los Angeles. While he knew it was not a solution to all the problems of South Central Los Angeles, it was his belief it would create a positive social impact. Youth Education Town, with Williams’ help, not only created positive public relations value for the National Football League, but more importantly, established a safe place for kids to study after school or on weekends with a myriad of opportunities to engage in sports and physical conditioning as well.

Williams’ Youth Education Town concept, and particularly its ability to have athletic competition on multiple playing fields, morphed into Disney’s ESPN Wide World of Sports complex. It became a home for amateur athletic competition from across the nation, if not the world. Williams became the first African-American vice president at Walt Disney World with the primary responsibility of developing the sports recreation business for the iconic entertainment brand. The facility became the home for professional sports teams like the Atlanta Braves which held training camp there. Moreover, Disney’s ESPN Wide World of Sports complex became the home of “the bubble” where the National Basketball Association finished its 2019-20 regular season and the 2020 playoffs.

To sum it up, Williams created opportunities for people and communities by compassionately evaluating the characteristics of the situations and events affecting them over his lifetime wherever he happened to find himself. Today, he continues to use his undying commitment to social justice to make positive change for individuals as well as communities by expending his time and energy on what he finds most important to everyone involved.

Listen to the new JARO podcast with Reggie Williams here.