NEW YORK (AP) — Ta-Nehisi Coates’ first novel, “The Water Dancer,” has been a long and eventful journey.

Begun a decade ago, his chronicle of a slave with an extraordinary memory who joins the Underground Railroad is the result of countless drafts, a shift from multiple narrators to a single voice, some needed advice from fellow writers and hundreds of thousands of words discarded. Coates’ research ranged from reading interviews with ex-slaves and consulting a 19th-century Farmer’s Almanac — books duly pictured on his Instagram account — to his numerous and revelatory visits to former plantations.

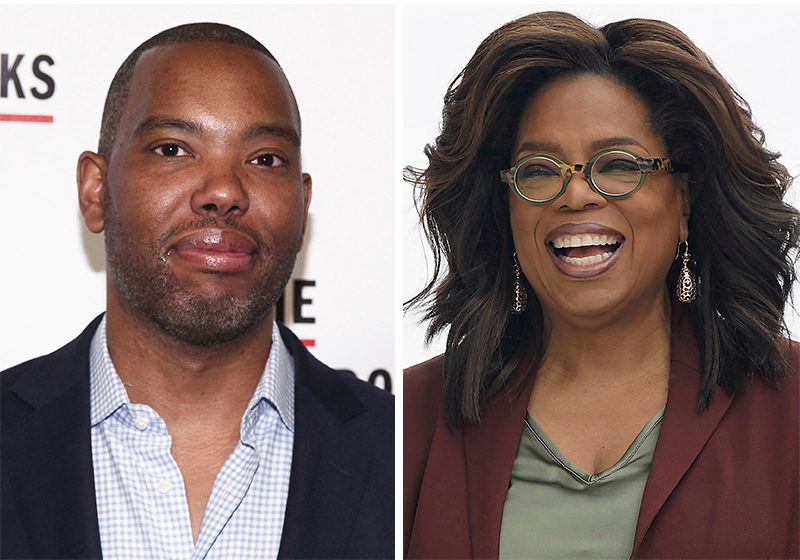

And then came that call from Oprah Winfrey.

“I was just as surprised as anybody. I pretty much write for myself and the only people I think about are my wife and my editor,” says Coates, whose novel is her latest book club pick. “I was really happy (about the news from Winfrey). But I think the most encouraging part was that she’s a reader. It was clear from the conversation that she’s a reader. This is not a marketing ploy. There’s nothing to be cynical about.”

Winfrey announced Monday that she chose “The Water Dancer” to formally begin her new book club partnership with Apple, for which she plans a selection every other month. In October, she will interview Coates before a live audience at Apple Carnegie Library in Washington, D.C., a conversation that will air Nov. 1 on Apple TV Plus, the new streaming service. During a recent telephone interview with The Associated Press, Winfrey became tearful as she described the novel’s emotional impact, how it captured the devastation and resilience of those enslaved.

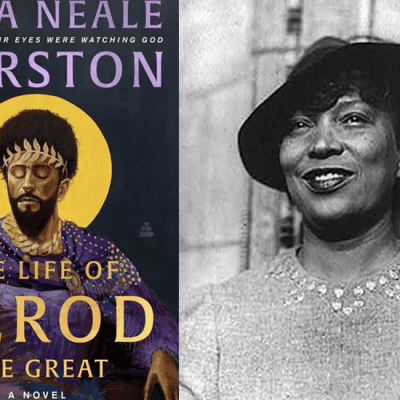

“I have not felt this way about a book since ‘Beloved,'” Winfrey said of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by her friend and literary idol Toni Morrison, who died in August.

The 43-year-old Coates spoke to The Associated Press during a recent afternoon at a SoHo cafe, where he drank strong iced coffee and received the occasional greeting from a friend or fellow customer. He said that he began the novel after completing his first book, the memoir “The Beautiful Struggle,” and acting on editor Chris Jackson’s suggestion that he try fiction. Jackson told the AP in a recent statement that “The Beautiful Struggle” demonstrated Coates’ “ability to dive so deeply and imaginatively into a character’s interior life and invent an idiom to tell the story that was more Joyce-ian than journalistic.” Coates, who had been reading extensively about the Civil War at the time, wanted to open readers to the “inner lives of enslaved black folks,” a “thriller” that would also dramatize the most profound questions of freedom and identity.

He worked off and on over the next few years on “The Water Dancer,” while honing a literary voice — of realism and poetry, outrage and exploration — that Morrison would liken to James Baldwin’s. As a national correspondent for The Atlantic, he wrote a highly influential and debated piece on reparations for blacks. He received a Hugo nomination for his contribution to the newly launched Black Panther comics series, “A Nation Under Our Feet.” In 2015, he published “Between the World and Me,” a letter to his son about being black in the United States that won the National Book Award, topped The New York Times best-seller list and helped confirm his status as one of the country’s leading social commentators.

“It wasn’t really that difficult,” he said of finding time for his novel. “I really liked writing ‘The Water Dancer.’ It was like I get to go play again.”

Winfrey’s original book club was started in 1996. She has since helped turn dozens of books into best-sellers, from novels by William Faulkner to a memoir by Sidney Poitier. For “The Water Dancer” and her upcoming choices, Apple has pledged that for each copy purchased through Apple Books, it will make a contribution to the American Library Association to support local libraries.

Winfrey said she was wary at first of “The Water Dancer,” if only because she found Coates such a “beautiful essayist” and wondered if he could move beyond the factual world. Journalists from George Orwell to Tom Wolfe have found success as novelists, but the switch from nonfiction to fiction can frustrate the most gifted writer. Nonfiction doesn’t only require adherence to the truth, but a kind of control over the narrative that the fiction writer has to surrender, at least in part. Novelists often speak of their stories becoming so real to them that a given character might lead them in a direction they hadn’t otherwise intended. Coates felt that with the protagonist of “The Water Dancer,” Hiram Walker, who did not start out at the center of the story, or even with the name Hiram.

“I really liked his story, and I said, ‘This is it,'” Coates explained.

While working on the book, Coates showed early drafts to peers such as novelist Michael Chabon, who suggested he “paint the whole scene,” Coates recalls, tell everything from how the sunlight looks in the trees to the smell of the air. “The Water Dancer” combines the most everyday details and the freest stretches of imagination, from the supernatural quality of Hiram’s mind to his encounters with historical figures such as the abolitionist Harriet Tubman. Coates’ favorite authors include E.L. Doctorow, known for mixing real and fictional people in such historical novels as “Ragtime,” and Morrison.

“She just had this mastery of the sentence,” Coates said of the late Nobel laureate. “She had a beautiful economy of words. I don’t that mean that in the sense that she was a sparse writer; she filled every sentence with so much emotion and feeling and information — visceral information, literary information. She wrote the way poets write. I took that from her early on.”

Coates, who says he has many ideas for another novel, left The Atlantic in 2018 and has no plans to resume his journalistic career. But even while working on fiction, he was reminded of the importance of reporting and the difference between reading about a subject and absorbing it on sight, how “you have to be there in order to feel it, in a way you can’t through books.” Coates cited the importance of actually standing on plantations and Civil War battlefields, notably a trip last year to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“The house is beautiful, stunning, gorgeous — and it was enslaved people who built it,” he says. “There’s a tunnel under Monticello that enslaved people walked through. When I walked through that tunnel, it was like, ‘Man, I get it now.’ I could see so much. I could feel my people talking to me at that point. I could feel it. But that was after 10 years of work. I don’t know how it happens without that.”