Netflix’s flagship original show, Orange is the New Black, returned for its sixth season – this time withthe women of Litchfield now in maximum security prison facing the prospect of additional time due to last season’s riot. Bonds that were formed in MCC’s minimum security prison are broken as “families” are divided into warring blocks with deep and long standing factions. Upon arriving in their new “home” the women are forced to decide between accepting trumped up charges as penance for the riot, or providing false, scripted testimonies against their friends. This season acts as the culmination of a tonal shift that slowly progressed over the life of the show. Whether this shift is intentional or not, Orange, has gone from a semi-comedic trauma porn that sought to critique the American prison system to a satirical parody that (somewhat) does.

Understanding the show as exaggerated satire is seemingly the only way viewers can accept the clean dovetailing of its multithreaded storyline. Daya’s mother, Aleida, has been out of prison for an entire season and unable to find the employment she needs to save money and rescue her other children from foster care. A guard at the prison takes a liking to her and she seizes the opportunity to secure a place for her to live and to generate income. After unknowingly transporting drugs into the prison, Aleida preys on her guard boyfriend’s insecurity and in a two minute conversation where she basically calls him a coward, she convinces him to willfully participate. This entire scenario does not feel realistic and reads from the writing standpoint as convenient. However, when looked at through the lens of parody and/or satire it highlights what appears to be the unfulfilling nature of working as a prison guard.

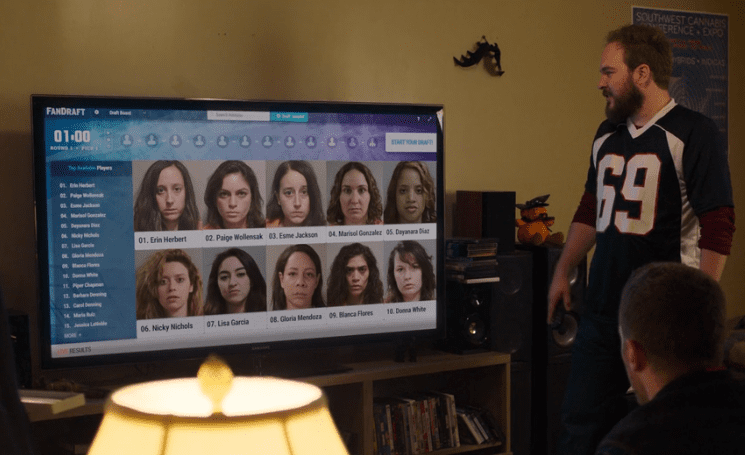

This satirical lens also helps us to make sense of the oversimplification of the characters – especially the prison guards. While it makes sense that years on the job may result in increased levels of desensitization, the guards with their gameof Fantasy Inmate, seem to be completely heartless. Modeled after fantasy football, guards draft inmates to their teams and win points (and hopefully money) based on their experiences – crying in the shower, sickness, assaults. The majority of the guards participate in the game and use their power and position to instigate and secure more points. They respond to stabbings and suicide attempts with cheers as it increases their chances of winning. By accepting this as satire, the show illustrates the deep-rooted cruelty of capitalism and it relationship to and dependency on the prison-industrial complex. It highlights how this mentality is embodied and enacted on the ground with the guards, as well as with the executives who attempt to evade public criticism through rebranding.

It is not certain whether this satirical parodic tone is effective or if it further problematizes representations of the nature of the American prison system. But one thing is for sure – Piper, the epitome of white privilege, is still annoying.