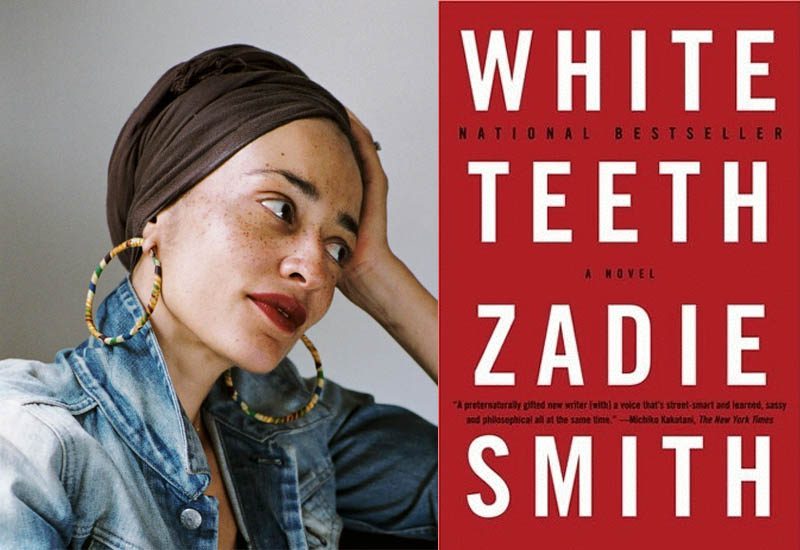

Remarkably, Zadie Smith was only in her early twenties when she wrote and published her debut White Teeth, a vigorous and spirited novel that critics and readers alike celebrate. It is considered to be a monumental work in the genre of literary fiction, featuring the art of bold, innovative storytelling. With her sharply created characters, Smith merges distinct cultural backgrounds together and masterfully writes a vibrant portrait of their lives in the heart of England during the late 20th century. The extensive novel follows the families of wartime friends Samad Iqbal and Archie Jones, and the trials that arise from raising Bangladeshi and interracial children in North London.

Considering its synopsis alone, I was not enticed to read White Teeth. My apprehension stemmed from the story being potentially convoluted as the timelines are not always linear; and while they hold invaluable weight, novels that have significant themes of war and politics have never been a personal preference. But only a riveting storyteller such as Smith can persuade me that perhaps my reading tendencies need to be reevaluated, as White Teeth was wildly entertaining (specifically in the first half), even with heavy political saturation. This can be attributed to the most impressive use of dialogue that I have ever come across in literature thus far; fleshed out characters leap off the page as reflections of legitimate humans, with their distinct senses of humor and individual cadences influenced by their culture. There’s the spouses of Archie and Samad––Clara Jones and Alsana Iqbal––and the intriguing second generation children: paradoxical twins Millat and Magid Iqbal, and the candid Irie Jones. The richness of the characters’ lives fuse the countries of Bangladesh, Jamaica, and England together, and friendship is discovered in an era and city where this is unexpected. Smith does a phenomenal job illustrating how there are no borders to be found in true soul connection, while also spotlighting the plights of the immigrant experience and the complex assimilation of Millat and Magid.

Yet as the fascination with Smith’s nimble style of writing dialogue began to subside around the halfway point, my attention was then fully dedicated to the narrative that was, to my dismay, developing in what appeared to be an unfavorable way. Becoming increasingly more dense and disorganized, it seemed as though this once enjoyable journey had fallen victim to the grip of distractions, losing its way due to the pursuit of side quests. On the right side of the road, for instance, there’s a passionate man who is giving an unbearably long and rambling monologue about his religious extremist group, and yes, the entire speech (along with the group’s history) must all be included; no detail will be spared! Move a bit further down the road and we’re nearing the end of this expedition. Ah, a perfect time to possibly regroup and return to the lives of our main characters. What happened to Clara? But wait! There’s an English family, the Chalfens, that reside in this house on the left of the street, and although they lack the same depth that our flawed but beloved protagonists have, why not give them an excessive amount of attention, too?

On my own personal journey, I would have instead followed Irie into adulthood, and watched what became of the Iqbal twins––three storylines with massive potential that were left with much to be desired. To be fair, arguably each new character and every detour served its own purpose in shaping the lives of our main protagonists. But as the book edged closer to its conclusion, I found myself deeply uninterested in the route it had taken, which resulted in an irresistible urge to skim over multiple sections that were jam-packed with cumbersome details about topics that failed to hold my intrigue. Thus, to reach the end of White Teeth became an arduous and unsatisfying act that required incredible stamina.

Though I wasn’t always engaged by the narrative, Smith’s witty tone and playful, uniquely clever use of language and dialogue ultimately served as the novel’s savior. Amusing yet dark and unsettling at times, White Teeth touches on every aspect of the human experience, regardless of the culture that provided us with our roots: the pain, the joy, those uncomfortable moments in between a specific feeling. What it means to go on, to find ourselves on the other side of suffering and to be met with a ray of hope. Despite the book being what could be considered an acquired taste within the realm of literary fiction, it is above all a mighty debut novel with great heart, perception, and understanding.