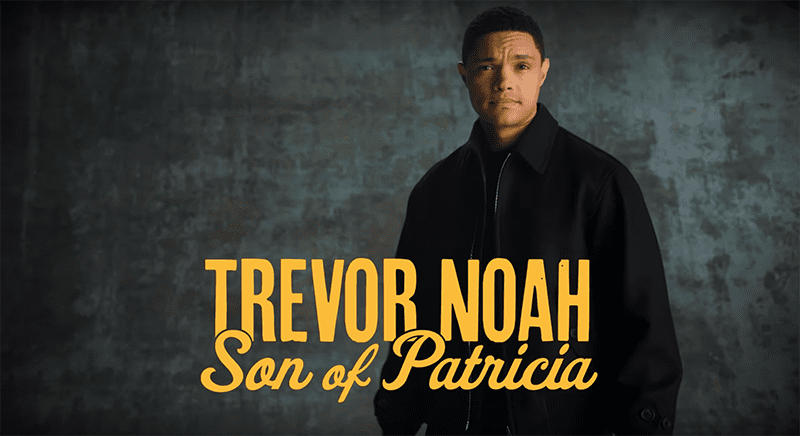

In his latest stand-up special, Daily Show star Trevor Noah continues to do what he does best – making us think about intersectionality while we laugh. Through the course of his one-hour special the barrier-breaking comedian takes us through his vacation in Indonesia, his life growing up in apartheid South Africa, and his strange encounters living and working all across the United States. While his comedic style is not as dark or straight-for-the-jugular as some of his contemporaries, Noah’s critical reflection provides interesting and comical commentary on culture, beliefs, and interpersonal relationships.

Noah’s strength as a comedian is his ability to function as both an insider and outsider. Growing up as a mixed-race child in apartheid South Africa, Noah’s very existence was a crime – something he often discusses in his work. Noah has firsthand experience with institutionalized racism and argues that of all the countries in the world, South Africa does it best. This legalized and social discrimination is an experience that allows him to connect with black persons across the diaspora. However, what is most interesting is that although he uses the shared experience of racism to relate to and with others, he then describes the nuances of his South African context. The comedian’s ability to build community and rapport across oceans while still allowing for individual experiences to emerge illustrates his penchant for comedy and fulfills a need for increased diversity among black experiences.

One of my favorite bits from the special is when he explains his relationship to the word nigger as a black South African. From explaining its meaning – “to give” in his home language, Xhosa to offering what could potentially function as the South African equivalent – kaffir, Noah uses language and culture to provide a somewhat subtle mediation on the stupidity of racism. In doing so, he also provides a comedic, yet possibly effective way of dealing with white supremacy. He argues that we should send racist white people to South Africa where upon landing they can call every black person they see a “nigger” seeing as how outside of its American context the word does not hold the same power. Noah’s imagined cultural exchange program at surface can seem a bit insensitive, but it really is a complex critique of white supremacy that puts racist whites at the butt of the joke. Noah offers another method for combating racism inspired by an experience he had in the States. In an interaction with an impatient racist white driver as he is walking across the street, Noah uses his mother’s advice of mixing up hate with the love of Jesus, and smilingly tosses the racial slur, back at the offender who stares at his hands in bewilderment.

Ultimately, through the comedic delivery of his experiences, Noah offers us insightful and hilarious ways to use humor to combat racism. In doing so, he situates himself as a global citizen, acknowledging what is enhanced and what is lost in translating oneself across cultures and at the very least challenges us to reflect on the complex nature of our own intersectional identities.