By Ron Mwangaguhunga

From Frieze and VOLTA to Art Basel and the Dakar Biennale, the 2022 art festival season was blazing hot, as this year has thus far been groundbreaking for diaspora art. After two painful years of lockdowns as well as halfhearted lockdowns, exhibitions have started to open up again, just like they did in the before times. Black artists, in response, are stepping up their game. American artist Simone Leigh and the UK’s Sonia Boyce won Golden Lions and were the first Black women to represent their nations at the 59th Venice Biennale. Also, Uganda, a first-time exhibitor won special mention at the 127-year-old art festival. At colleges and gallery panels throughout the summer discussions were popping up on the art of the diaspora, on who should own it and why it matters.

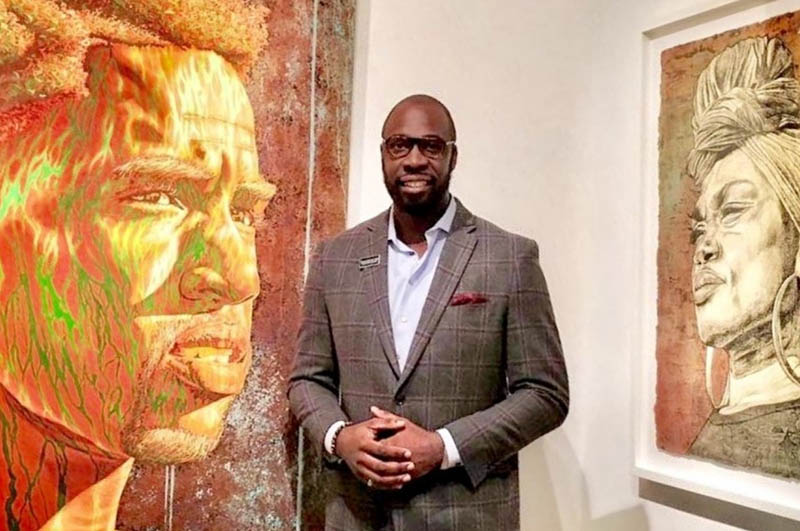

This is a golden age to be an art dealer focusing on African diasporic art. Somali-French art dealer, Mariane Ibrahim, for example, was recently featured on CNN’s “Nomad with Carlton McCoy” and The New York Times. As one of the few black gallerists in Paris, one focusing on Afro-diasporic art, Ibrahim has featured the works of Ghanaian painter Amoako Boafa . Three of Boafa ‘s paintings were literally headed for the stars, aboard Jeff Bezos’s suborbital rocket built by Blue Origin. Further, Boafa one of the most sought-after diaspora artists (his yellow saturated “Hands Up” sold for $3 million in March), has Souls of Black Folks his first museum solo exhibition on view at the Contemporary Art Museum of Houston . As the Brown Foundation gallery website notes, “Boafo creates paintings that actively center Black subjectivity, Black joy, and the Black gaze.” It continues, noting his critically acclaimed brushwork. “The brushstrokes of his vibrant portraits are thick and gestural,” the site observes, “the finger technique emphasizing the contours and luminous skin tone of the body.” The exhibition, which takes its name from the most important work of sociologist and noted Pan Africanist WEB DuBois, started in Houston on May 27th running through Oct 2nd.

What was the modern turning point in Afro-diasporic art? When, precisely, during the civil rights revolution did black art globally gain respect and not just cultural appropriation? It was around the time that African diaspora studies began to be taken seriously as a topic of concentrated studies at American and European universities. Robert Farris Thompson, one of the mentors of historian Henry Louis Gates, was perhaps the most influential pioneer in categorizing African diaspora art. His seminal defense of African-American art in 1969 and his arguments on how to view Afro-diasporic art in dynamic motion, not static, inspired the influential 1974 installation “African Art and Motion” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. From May 5th to September 22, 1974. The National Art Gallery, supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, presented diasporic art accompanied by continuous film, audio recordings showing works specifically used in dance or ceremony. Gaillard F. Ravenel, George Sexton, and James F. Silberman did the elaborate installations that were seen by hundreds of thousands of viewers. Afro-diasporic art has only gained in cultural relevance and value since then.

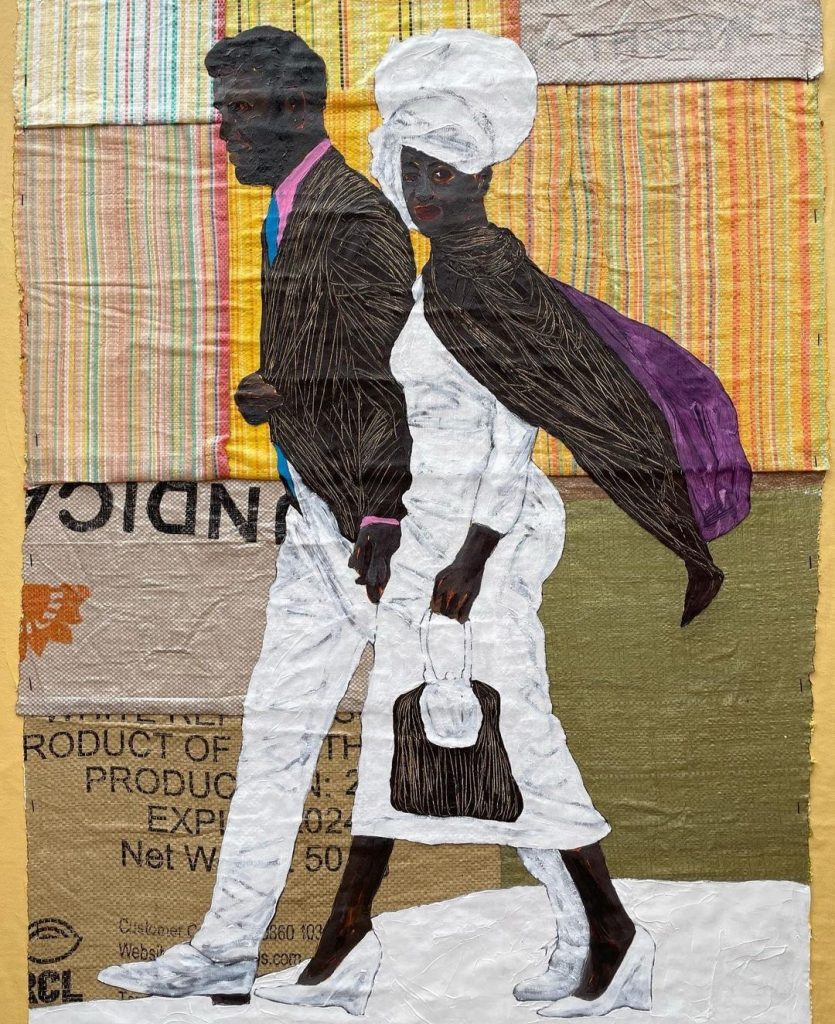

How is the sensible curator supposed to distill four centuries of diverse works and styles in multiple media from different countries along the diaspora into a coherent conversation with one another? It seems an almost impossible task. “Afro-Atlantic Histories” that was on view at the National Gallery of Art this summer appeared to have come up with a solution. The show was thematically arranged, allowing a narrative to emerge among the more than 130 works of art from artists spanning Europe, the Americas and the Afro-Caribbean. “It’s a plural word,” National Gallery of Art’s new Curator Kanitra Fletcher explained to Jonathan Capehart of MSNBC about the show’s title:

“It’s speaking to the plurality of the voices of the lives and experiences that have all contributed to the African diaspora. So we are really resisting a Grand Narrative of a singular way of understanding the African diaspora. We are refusing hierarchies, including … of media. There’s painting and sculpture, photography, works on paper, textiles, all coming together and on equal footing.”

There was so much to see in diasporic art this summer. Basquiat’s Wicker on view for the first time at The Broad Museum in Los Angeles is still running, and on the other coast, Basquiat’s King Pleasure show, curated by his mother and sisters, at the Starrett-Lehigh building in Chelsea, New York has been drawing raves. On May 5th, British artist Isaac Julien’s True North opened at Ruby City in San Antonio, Texas. The multi-screen installation honors African American explorer Matthew Hensen, thought to be the first to reach the North Pole. Was he? That is the question the installation seeks to answer.

Some of those conversations raised by Afro-diasporic approaches can be uncomfortable. Hank Willis Thomas reveled in those types of conversations in his work. Born in 1976, Thomas raises difficult questions around identity, as do many diasporic artists, but few have his intensity. In a 2020 piece of his titled A Place to Call Home (African American Reflection), the artist wrote in an artist statement, “This map points to feelings of connection and detachment that many African Americans have toward Africa,” he explained. “(It establishes) mythical connection to Africa is embedded in your identity, but many people go to Africa looking for home and don’t find it because our roots are so diluted there. They also never felt at home in the U.S., where they were born. I wanted to make a place where African Americans come from.” The piece is stainless steel with a mirrored finish. However uncomfortable the narrative becomes, the gallery space is the right space to have that important diasporic conversation.

BLACK VENUS that showed in Manhattan’s Fotografiska Museum is an exhibition that surveys the legacy of Black women in visual culture – from fetishized, colonial-era caricatures, to the present-day reclamation of the rich complexity of Black womanhood by 19 artists (of numerous nationalities and with birth years spanning 1942 to 1997). This exhibition is a celebration of Black beauty, an investigation into the many faces of Black femininity and the shaping of Black women in the public conscious – then and now. The show features works by some of the most influential Black women in contemporary art, including Renee Cox, Coreen Simpson, Deana Lawson, Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, and Ming Smith. Cox’s reimagining of Baartman, titled Hot-en-Tot, is particularly powerful, as it reclaims ownership of the Black female body by covering areas that were exploited by the white male gaze in the original painting.

The Public Art Fund backed sculptural group show Black Atlantic displayed on the shores of a former shipping port in Brooklyn was inspired by the diaspora across the ocean that connects Africa with the Americas and Europe. The show is running through November and features acclaimed artists Leilah Babirye, Hugh Hayden, Dozie Kanu, Tau Lewis and Kiyan Williams.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, is exhibiting at the National Arts Gallery. In Eko Skyscraper, the 39-year old Nigerian born and raised in Los Angeles — offers the viewer a 1967 photograph of a young Congolese woman bathed in orange. 45-year old Afro-Cameroonian artists Fred Ebami is another such trailblazer and, Copenhagen-based, Danish-Trinidadian artist Jeanette Ehlers is an Afro futurist force to be reckoned with. Elher’s works tackling the great turning points in Black history and whose cinematic universes addressing the history of colonialism and structures of racism are truly mind-blowing. Her exhibition Black Bullets at Espoo Museum of Modern Art in Finland was on view from May 10th August 14th capturing the moment the Haitian and French forces clashed in the 18th century.

Tracey Rose’s radical show Shooting Down Babylon at Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town that run though August 18th was politically exciting.

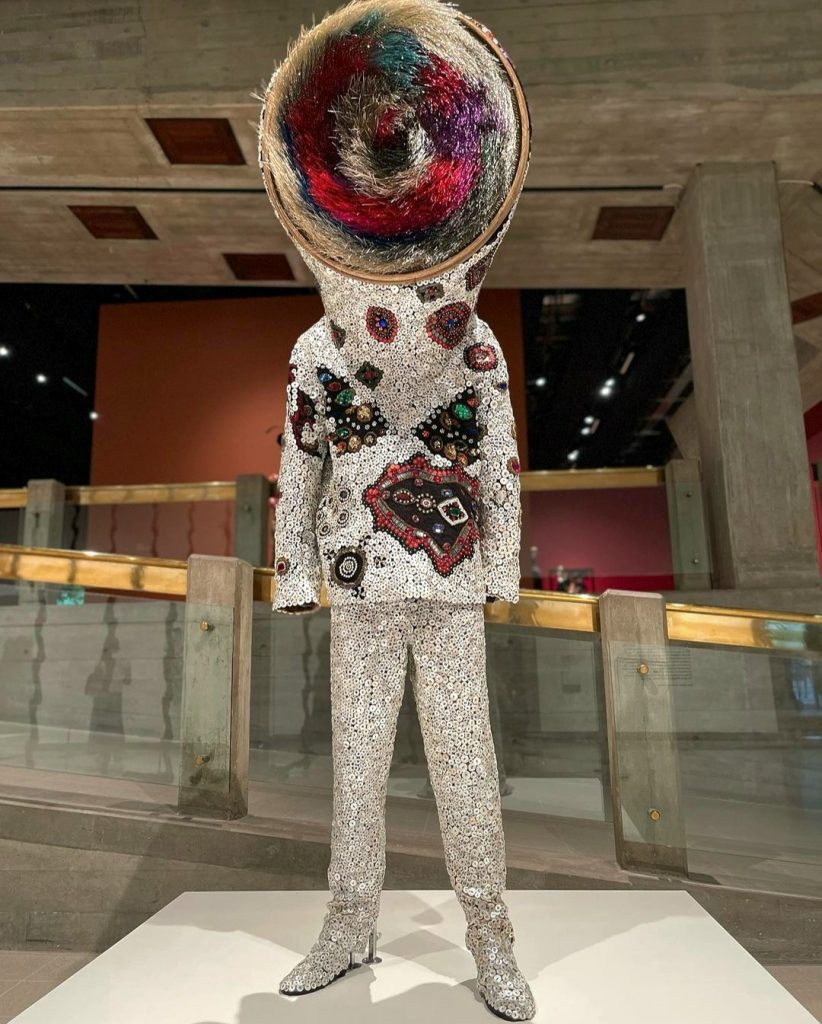

In The Black Fantastic exhibition curated by Ekow Eshun at the Hayward Gallery in London on view through September 18th features 11 diaspora artists, including Nick Cave, Sedrick Chisom, Ellen Gallagher, Hew Locke, Wangechi Mutu, Rashaad Newsome, Chris Ofili, Tabita Rezaire, Cauleen Smith, Lina Iris Viktor and Kara Walker.

“Each artist is given the equivalent of a solo show in a separate space, painted in the richest glowing colours,” writes Laura Cumming in The Guardian.

Multitudinous is the breadth and complexity of art to be seen from the African diaspora. It is a great ocean of works that span geographic space and time. It includes artists from Africa from across the Atlantic from the 17th century to the present. The themes and subject matter are as diverse as meditations of the brutality of the forced transatlantic slave trade to afro-contemporary photography, to Afrofururist NFTs to the new, Afropolitan sensibility – as well as everything in between.

The long, hot summer of Black art was epic and is still raging through the fall.

Ron Mwangaguhunga is a Brooklyn based writer on media, culture and politics. His work has appeared within Huffington Post, IFC and Tribeca Film Festival, Kenneth Cole AWEARNESS, NY Magazine, Paper Magazine, CBS News.com and National Review online to name a few. He is currently the editor of the Corsair.